the Squires’ tower

This is one of the four towers which once framed one of the three entrances to the primitive fortress. It belonged in the 16th century to the squire Olivier de Surville, co-lord of Gras and Saint-Montan, then in the 17th century to the squire Claude de la Teulle, his nephew, lord of la Combe in 1606 whose seigniorial house and the garden occupied a large part of the adjacent land.

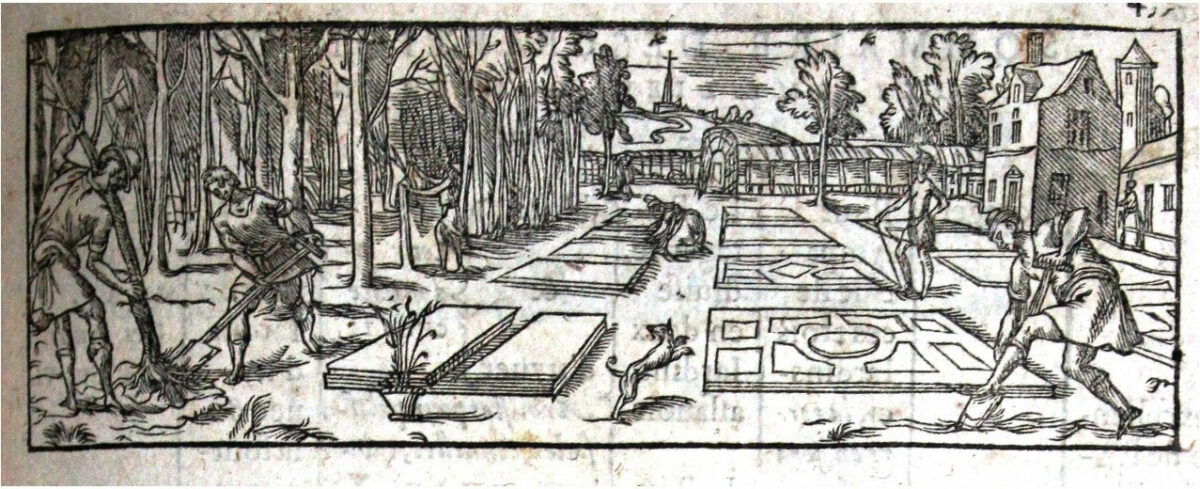

the Survilles’ garden

This garden has been mentioned since 1592. It belonged to the squire Olivier de Surville, co-lord of Gras and Saint-Montan, owner of the stately house now in ruins which dominates it. In 1624, it was the property of Jean de Mottet, then of Jean Pierre de Mottet, finally Baptiste Vergier in 1674.

the chapel of the penitents

Originally this 11th-12th century building was the aula (lordly dwelling) of the primitive castle belonging to the Saint Montan family.

In 1594 it was a common house, then around 1620 it became a chapel of penitents until the Revolution, finally a common house again where the first republican mayor of Saint-Montan, Jean Claude Joseph de Saint Priest, was elected before, finally, being abandoned and used as a stone quarry.

The chapel of the white penitents of Confalon (under the patronage of Sainte-Catherine) probably founded around 1620 on the initiative of Claude de Benoît lord of Saint-Montan on the model of that of Avignon where he came from, was internally vaulted in a pointed arch, coated with fine mortar brushed white a bit like stucco, separated into two parts: the smaller one, on the west side which overlooked the outside and located under the bell tower, was equipped with a built bench covered with terracotta tiles on the northeast side where “all useful things for maintenance and service were kept”, the most spacious called “large chapel” reserved for divine service included a stone altar on a stone platform attached to the wall Oriental. The floor was terracotta tiles measuring 15.5 x 15.5 cm. There was at least one painting with a frame given by Anne de Banne de Boissy, co-lord of Saint-Montan. In the monumental bell tower, above the entrance, there was a bell weighing just over 100 pounds (around 45 kg).

In January 1621 this bell was cast on site for which we have the estimate and payment of the invoice.

the ancient keep

(or fortified tower)

The word keep (donjon in French) refers to a large defensive tower within fortified residences built by European nobility during the Middle Ages. The towers were used as a refuge of last resort should the rest of the castle fall to an adversary.

This quadrangular tower of Saracen style is the oldest part of the existing castle of SaintMontan and may date back to the 11th century. Initially square, it was later enlarged on its eastern side. It is currently 15 m high with a total ground surface of approximately 60 m², and an inner surface of 40 m², the walls being 1 to 1.5 m thick. It has four levels separated by wooden floors previously accessible by ladders.

Originally a component of the ancient castle and connected to the lords reception hall (now the chapel of the penitents), one entered the keep through an elevated doorway – now walled up but still visible – on the eastern side. The opening of the current entrance was made in the 14th century, when the keep was included in the courtyard of the second castle.

The keep was never a residence of the feudal lords, but solely designed for defensive purposes, as can be seen by the absence of any comfort facilities or large windows and the presence of numerous arrowslits, crenels and battlements, mainly on the west side which corresponded to the outer side of the ancient citadel.

During clearing work by volunteers in the Rue de Clastre, at the foot of the southeastern corner of this keep, the remains of five men, killed at the end of the Wars of Religion, were discovered. (On the photo one can see two of them).

the cistern

The cistern occupies the ground floor of the northernmost building of the seigneurial residence. It is partly dug into the rock which in places has been disbursed over more than 2 m. It has a maximum capacity of 40 m2 and is made up of two basins coated with tile mortar similar to that used in Roman aqueducts to ensure its watertightness.

In the past, the first pool was probably fed by a now dried-up spring which gushed through a crack in the rock.

The second basin of the cistern was fed by rainwater which was collected from the roofs and from the main courtyard by a system of channels directed towards a funnel-shaped opening which was located just to the right of the door. of the servants dormitory. It was perhaps covered by a slatted floor which could keep certain fragile foods cool.

Water was drawn from the first basin from the main courtyard using a pulley and a bucket through the opening facing the kitchen door. The latter was closed by a door in order to preserve the quality of the water.

The large door which gives direct access to the cistern from the esplanade is much more recent. Breakthrough for reasons that we do not know, it was never completed and this is the reason why it does not have a threshold.

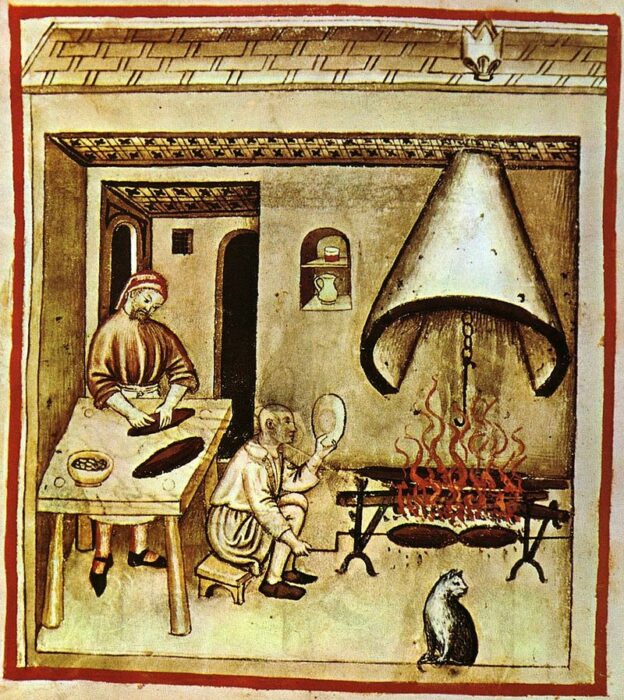

the medieval kitchen

The medieval kitchen dates from the 14th century. It was established in an extension of the 12th century keep (defensive tower) and is connected to the courtyard on one side and the dining hall on the other.

It is a basic kitchen without a fireplace and over the years and centuries it was never modified or modernized. Cooking was done on open fires on the floor (one can still see stones reddened by the heat in the south and west walls) and the smoke escaped through vents under the ceiling.

Commonly, in this type of medieval fortified castle there were no hearths with chimneys and this fortress was no exception. The rooms were heated by metal braziers containing a fire and placed near the windows and doorways.

The water used for cooking was drawn from the foremost reservoir of the cistern just across the inner courtyard. This reservoir was fed by a fountain that has since dried up. The second reservoir was filled with rainwater that was collected from the roofs by a system of troughs and channels.

the weapons room

(former dining hall)

The weapons room which was the dining hall or lower and more ancient hall on the ground floor of the 12th century fortress, with its Romanesque vaulted ceiling and flagstone floor dating from same period, served as a common space for meals as well as a dormitory for the inhabitants of the castle.

One could either set up trestle tables surrounded by benches, or unfold cots for the night. The adjacent documents show us that at the end of the 14th century, Catherine de Châteauneuf, who was then the lady of Saint-Montan, received the homage of the people under her dominion in this very hall.

The dining hall, with a direct access from the inner courtyard, was connected to the kitchen on its eastern side and, on the opposite side, by means of a wooden gangway, to the chemin de ronde, the patrol path along the third and inner ramparts.

The outer door and windows could be closed by wooden shutters and the windows were fitted with wrought iron grids to prevent the intrusion of possible assailants.

the Servants Dormitory

This room, placed above the cistern, was part of a military edifice, probably dating back to the 12th century.

Evidence of its defensive nature is found in the presence of an arrowslit overlooking the inner courtyard, as well as in a doorway once leading to the patrol path along the ramparts by a wooden passageway that has since disappeared and finally in the remnants in the north-west corner of a bretèche or brattice (a small balcony with an open floor through which stones or boiling water could be dropped on attackers huddled at the base of the fortress). There is now a window in the wall facing the hillside where the bretèche used to be.

In addition to its defensive use, the space also served as living quarters, as illustrated by two alcoves, dating from the 13th century, that served as cupboards the bigger one with an arch of carved stones and by the latrines at the start of the chemin de ronde, the patrol path along the ramparts.

The rather massive wooden framework of the ceiling was initially designed to uphold a covering of flat limestone slabs. These were replaced by Romanesque roof tiles during repair work on the castle starting in 1611 under supervision of the then reigning lord.

The servants slept on straw mattresses on the floor, lined up one next to the other.

the Justice Chamber

The Justice Chamber, located on the second floor of the 12th century fortress, was where justice was rendered by the lord or his judge. It could also be used for receptions and as a banquet hall.

The high Gothic vault of limestone tufa dates from the 14th century and replaced the original wooden ceiling.

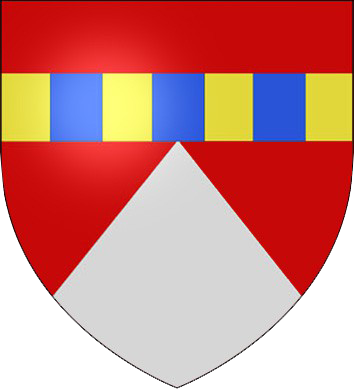

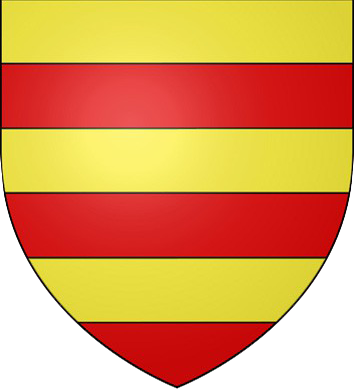

In the 14th century the main window of the room was adorned by six carved and painted coats of arms. The largest of these coats of arms was that of Marguerite du Tournel, feudal lady of Saint-Montan, and the second in size that of her successors, the family of Glandevès (also known as the house of Cuers).

During rehabilitation of the castle in 1611, the window, which was in poor condition, was renovated but the coats of arms were not replaced.

In its final state the floor of the room was bedecked with rectangular terracotta tiles laid in a herringbone pattern.

The cavities in the walls mark the remnants of putlog holes: holes made in the walls to receive the ends of poles or beams – called putlogs – to support the scaffolding for the construction. Putlog holes may extend through a wall to provide staging on both sides.

the lords chamber

The lords chamber dates from the 14th century. It was built above the kitchen (dating from the same era) and next to the justice room. Its wooden ceiling upheld a roof terrace.

This chamber served as a bedroom for the lord and his family, but also as a living space where he could consume his meals and rule over his seigneury.

The chamber contained a bed, seats, a working table and chests for archives and personal belongings.

The reproduction of the small painting shows us this very room with a four-poster bed in which the wife of the lord lies ailing. At the foot of the bed her husband is praying to Saint Montan, beseeching him to make her better. His wife recovered and as a mark of gratitude the lord commissioned this painting that was discovered in the old church in Saint-Montan. Notice the interesting garments.

The window was quite big for those days. From it, the lord had a perfect view of the outer courtyard, the ancient keep (defensive tower), the whole of the fortified village and its outskirts, as well as the Rhône valley and the perched and fortified village of La Garde Adhémar. Beyond the Rhône he could see the Drôme, in those days the dukedome of Valentinois under rule of the Holy Roman Empire (not to be confused with the Roman Empire) and beyond that, in the distance the Vaucluse, former Comtat Venaissain, land of the Pope, with the Mont Ventoux, 1912 m high.

The watchtower

The castle watchtower called “Tour Haute” is the highest point of the Saint-Montan fortress.

Its base is old and it was raised, probably at the start of the Hundred Years’ War, in the 14th century, like a large part of the walls.

The ground floor includes a small vaulted room used as a guard room from which a straight, steep and narrow staircase leads to the walkway. The upper floor includes a winding staircase giving access to the crenellated terrace on which is built a small gatehouse open to the east in which the watchman could protect himself from the sun, the rain and the north wind.

The watchtower, the Grand Tower (the original keep) as well as the walls of the castle already belonged to the community before 1609, while the other buildings of the latter remained the property of the lord castellan until the Revolution.

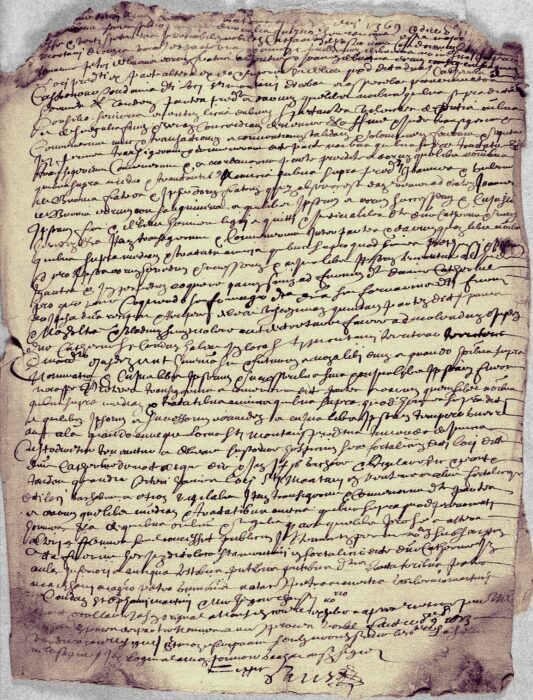

the house called

“le Canard”

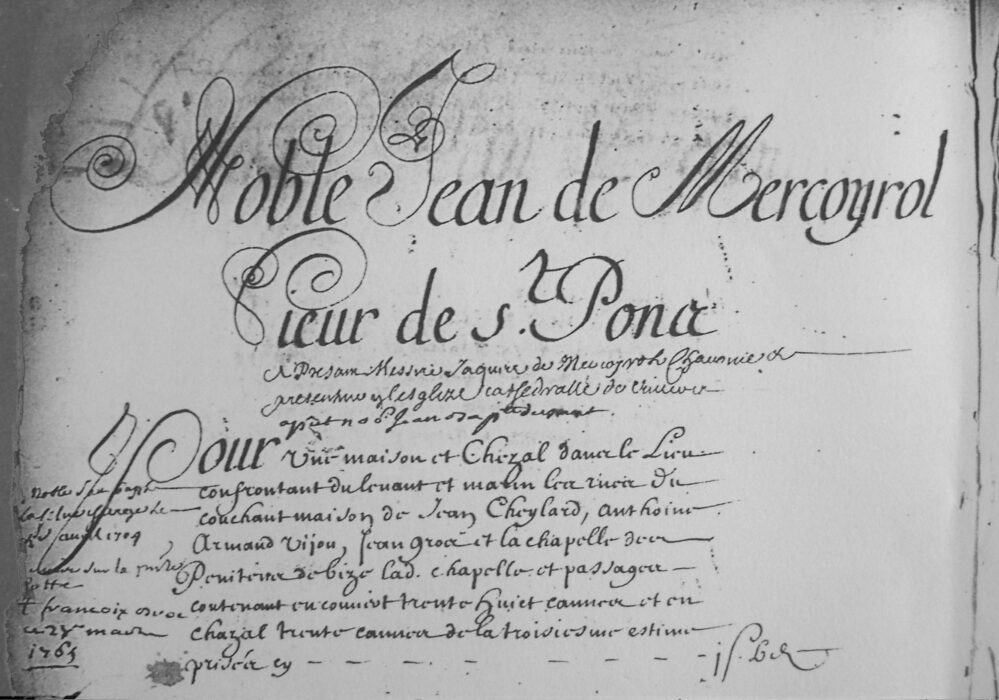

Stately house remodeled over the centuries, probably dating from the 12th century. In 1338 it would have belonged to Guillaume la Motte from the Balazuc family that we find co-lord of Saint-Montan as early as 1250. In 1592, il belonged to the Rey family, co-lord of Saint-Montan at the beginning of the 16th century. In the 17th century it belonged to Joachim, then Jean de Mercoyrol, co-lords of St-Montan from 1604 to at least 1684.

In addition, there was, at least at the beginning of the 18th century, a barracks as well as a prison.

A text from 1732 would lead us to believe that it was the so-called “le Canard” house for which we have an illustration of the cadastral description on the compoix (cadastral matrix) of 1674.

December 12, 1732

12 pounds and 16 sols for the necessary repairs to the house of Mr. de St Pons (Jean de Mercoyrol de Beaumevallier), (adjust the lock of the entrance door, close two doors and a window, the shutters of the large room, a frame and to half block two other windows, two hinges to carry the shutters) everything necessary to be able to accommodate the company in this barracks (a lieutenant, 2 sergeants, 38 soldiers), £1 and 13 sols to repair the prison door of the barracks or for a key that the accountant had made for the padlock that had been lent to him to close the door or for a piece of wood used to hold the frames closed.